About a month ago, a contact on LinkedIn posted a link to a TED talk by writer Oscar Schwartz, titled “Can a computer write poetry?” Schwartz is one of the co-creators of the site Bot or Not, where users are shown poetry before being asked to guess whether it was written by a human or a bot.

Some respondents on LinkedIn were open to the idea posed by the talk’s title. Some were even excited by it.

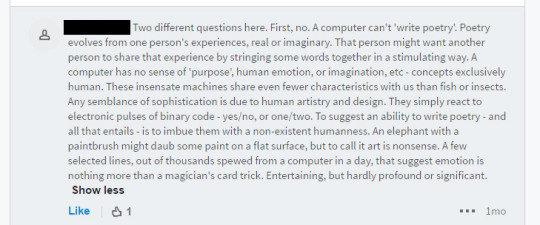

While some flatly refused to accept it was possible to create valid poetry in this way, for a variety of metaphysical, emotional or philosophical reasons.

Indeed, in the third response, the idea itself seems to provoke an emotionally charged response. This is frustrating. It’s kneejerk, assumes a narrowcast definition of poetry and seems to rule out the opportunities and potential for the marriage of programming and poetry.

The overall question explored by Schwartz’s TED talk (and PhD thesis) concerned the difference between poetry generated by humans and poetry generated by algorithms. In a live Turing test for poetry, Schwartz showed the audience several excerpts, asking them to guess which was human-authored and which came from a computer.

While most respondents guessed ‘human’ for William Blake, they cried replicant on more avant-garde poems by Frank O’Hara and Gertrude Stein. O’Hara’s fast-paced mishmash of everyday sights and Stein’s shifting repetition do give the impression of data being drawn and processed at speed. It’s that spontaneity and play that I particularly enjoy.

But is it play when a computer emulates it? Can a computer legitimately play, or is everything a response to a pre-programmed set of instructions? Does this matter?

More to the point, what is so sacred about poetry above other media that it is ringfenced as a cache of human “mood, passion and personality”? We have no trouble with bots creating copy (@MarkovChocolates) or play-testing our video games. Is this rejection of non-human poetry, as a friend suggested to me, a hangover from post-Enlightenment anxiety over art being subsumed by science?

I asked the same friend what he thought the respondents arguing for “heartfelt, gut-wrenching emotions” in poetry thought a poet looked like.

“Thin, on a hill somewhere, flowy shirt. Probably white.”

Likewise, if we asked non-specialists what they thought a robot looked like, chances are they would describe the metal humanoid of countless sci-fi epics.

The Japanese robotics expert Masahiro Mori has little interest in such beings. He eschews the race to create a passable artificial human as boring. In his 1981 book The Buddha in the Robot, he finds the seeds of a soul in all automata:

“I believe robots have the buddha-nature within them – that is, the potential for attaining buddhahood.”

Mori, responsible for the theory of the uncanny valley, has found himself able to apply his very human religious faith to the machines he works with. After all, something of the human is put into every line of code that guides them. His words bring to mind the Japanese folklore around tsukumogami, household objects that, upon completing 100 years of servitude, become animate and self-aware.

There is a real fear, echoed by scientists like Stephen Hawking, that conscious artificial intelligence will lead to robots creating robots and humans being superceded. Perhaps that is the real issue for the commenters. A fear of being replaced. There are numerous articles on whether a robot could put you out of your job as automation expands, and one of the comforts for garret-dwelling writers and artists is that according to such articles, their jobs seem low on the risk list. You can’t fake the feels, right? But while we have not yet managed to synthesise emotion, we have no idea how close such advances might be.

Or perhaps it is more a ‘Death of the Author’ issue, and unease at leaving a poem open to interaction and play by others (see Microsoft’s recent PR car crash with their chatbot @Tayandyou, thanks to the imps of Twitter). If we let our work out there, it might get corrupted. If we want our work out there, that’s a risk we have to take. One (hyphenated) word: Fan-fiction.

We should not approach computer-made art with such fear and hostility. Science fiction has a lot to answer for in terms of rogue robots setting upon humans and nightmarish images of man and machine being forcibly melded. But this same anxiety has played out in various guises throughout history, substituting robots for any ‘other’ present among a majority. What if it was just our ideas that joined together? What if the computer was as much a collaborator and contributor as the human?

3D artist Matthew Plummer-Fernandez goes even further. His sculptures are created through coding, so that the final product is almost an afterthought, printed out for exhibitions. In an interview I conducted with him a few years back for Maker World magazine, he said

“I actually try and engineer out the human as much as possible. I find so much media art really human-centric. But I find more fascinating computer systems that have this behind-the-scenes air, constantly doing things without any human interaction, sort of left to their own devices.”

In freaking out at the prospect of a robot poet, poetry lovers are forgetting a few key things:

i) Poetry cannot exist in a vacuum. Poetry needs to broaden its audience. It needs to speak with other genres, media and audiences in order to not just survive but thrive. Computer poetry, like cut-ups and Oulipo experiments before it, offers one way to explore this.

ii)

It’s happening already. Twitter is full of bots tirelessly remixing and generating text, creating accidental poems as they go. For me, intent is secondary. See also The Literary Operator, a device created by programmer Tom Armitage and sci-fi author Jeff Noon to scan and digest books, and spit out a remixed, abstract impression of each title. See also the thousands of projects around the world in which computers participate in the creation of art.

iii)

Computer-generated poetry is for all. It needn’t be portcullised by the need for coding skills – in fact, it could be an excellent excuse to bridge the artificial science-art gap and collaborate. As a gateway into poetry, technology can include a larger range of would-be authors and welcome people who might otherwise feel excluded. Whether this is due to a disability, language barrier or personal preference, the intervention of technology could engage and befriend new fans of poetry. Indeed, framing poetry as a game or coding exercise could, as with the tsukumogami, bring it to life.

Do you, for one, welcome our new robot overbards? Or does real poetry only come from fleshlings? Comment below.