‘I could tell you my adventures-beginning from this morning,’ said Alice, a little timidly: ‘but it’s no use going back to yesterday, because I was a different person then.’

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

When Jim Henson’s fantasy adventure Labyrinth made it to TV in the late 80s, I would have been around 6 or 7. Most older millennials will have encountered this epic at some point, if only in the context of David Bowie’s enchanting balls.

If you’re new to the movie, it starred a 14-year-old Jennifer Connolly as Sarah, a daydreaming suburban girl who idly wishes for Jareth, King of the Goblins (Bowie), to take away her baby brother Toby, only to find her wish granted. Thrown into Jareth’s magical labyrinth, Sarah must reach his castle before 13 hours pass and Toby is turned into a goblin.

I began with an Alice in Wonderland quote, but it could just as easily have been The Wizard of Oz, as all of these narratives involve a young girl finding herself in a strange land. But where Dorothy was cheery and upbeat in Oz and Alice retained a sense of grumpy clarity, Sarah nearly loses herself entirely to the labyrinth.

SPOILERS: I recommend watching the movie before reading this article, as I’m going to do a deep dive of plotpoints.

Labyrinth was thrilling to me as a kid – not just because of the chemistry between Bowie and Connolly, nor the epic puppeteering and monsters, and not even for THAT dress (although I do still want it), but because Sarah’s journey through the labyrinth spoke to me emotionally. Specifically, her mistakes, her frustrations, the friendships she forged, and her refusal, in the end, to give up.

Fast-forward to 2021. It’s been a year since I received the ADHD diagnosis that caused so much to fall into place for me. I find myself returning to Labyrinth to view it through a neurodivergent lens – particularly as someone who, until last year, felt just as lost as Sarah. Here are five ways in which this camp, glorious movie sang to my weird brain.

1. Sarah the daydreamer

When we first meet Sarah, she is running around a park in her hometown wearing a princess costume over jeans and quoting from a book titled Labyrinth. She struggles to remember a monologue from the book, and this will return to haunt her later. As a kid I would bike round and round the same patch of tarmac for hours, making up fantasy stories and dressing up for, like, no reason.

Sarah’s reverie is interrupted by the chiming town clock: she’s late home to babysit her stepbrother. She runs home in the rain, no longer a proud princess but a little kid wailing: “It’s not fair!”

Later on, this hyperfocus is manifested magically in the amnesia peach Jareth tricks Hoggle into giving to Sarah. She loses consciousness and precious time, dreaming she’s at a masquerade ball with the Goblin King. Despite her beautiful dress and Jareth’s serenade, there is a hostility in the air – she knows she should be somewhere else.

2. Friends and foes of Sarah’s own making

If the labyrinth seems tailor-made to torment Sarah, that’s because it is. Every character we meet expresses dual facets of her personality – traits which are very familiar to folk with ADHD. Let’s look at her friends first:

Hoggle

Hoggle: [sadly, after Sarah eats the amnesia peach] Oh, she’ll never forgive me. What have I done? I’ve lost my only friend. That’s what I’ve done.

Hoggle is a self-confessed coward, desperate for friendship and full of self-loathing. He is riddled with anxiety and prone to catastrophising, but when the chips are down, he’s resourceful, decisive and prepared to face his greatest fears to help Sarah.

Ludo

Ludo is a gentle giant, often mistaken for a fierce monster. He is lonely, clumsy and misunderstood, but also loyal, hard-working and intrepid, lacking only leadership. He also has a unique ability to summon rocks, which comes in surprisingly handy later on!

Sir Didymus

Sir Didymus is something of a jobsworth, tasked with guarding a tiny bridge. He over-adheres to rules, regardless of logic and misses obvious things (for one thing, he’s unable to smell the Bog of Eternal Stench), but once Sarah has earned his trust, this plucky terrier fights valiantly for his friends.

And now a few foes:

The Goblins

The goblins are Jareth’s omnipresent agents, embodying both the unrestrained impulsivity and the chaotic disorder that sabotage an ADHD brain. They hide things, stop things working, aid the forces working against Sarah and put catchy songs in her head when she’s trying to concentrate, damnit.

The Fire Gang (Fireys)

“Chilly down with the fire gang /

Think small with the fire gang”

‘Chilly Down’, Labyrinth OST

The Fire Gang, or Fireys, are a manifestation of extreme distraction as a destructive force, with a side of rejection sensitivity. Hard-partying orange fuzzballs, their bodies come apart and reconstruct like Lego, and they surround Sarah in order to bamboozle and stall her. The demons have big smiles but sharp teeth, and just as the pretty poppies in Oz nearly drug and doom Dorothy, their catchy song ‘Chilly Down’ half-hypnotises Sarah. It’s only when she shakes herself loose and tries to escape that they become malevolent, attempting to take off her head before she escapes. It’s perhaps no coincidence that “Off with her head!” is the frequent cry of Wonderland’s Queen of Hearts when anyone displeases her for a moment.

Jareth, the Goblin King

Jareth: Turn back, Sarah. Turn back before it’s too late.

Sarah: I can’t. Don’t you understand I can’t?

Jareth: What a pity.

I’ve left Jareth till last here because he is Sarah’s dysfunction personified. He sows doubt and confusion, manipulates time and order, mocks her, takes advantage of her impulsive wishes, plays cruel tricks, drives wedges between her and her friends, and tries everything to make her lose heart. And all the while, he works to convince her that his rules are the only rules by which she is allowed to play.

Sarah: It’s not fair…

Jareth: You say that so often, I wonder what your basis for comparison is?

When direct attack doesn’t work, he effectively drugs her to forget the pain of her quest. It is only by smashing through the facade of the masquerade ballroom that she sees things as they really are: her childhood belongings and pastimes are weighing her down and she must leave their hollow comforts behind to save Toby and make things right.

Unsurprisingly, when he is on the cusp of being beaten and Sarah questions his self-declared ‘generosity’, Jareth lashes out:

Jareth: Everything that you wanted I have done. You asked that the child be taken. I took him. You cowered before me, I was frightening. I have reordered time. I have turned the world upside down, and I have done it all for you! I am exhausted from living up to your expectations of me. Isn’t that generous?

This “after all I’ve done for you” speech feels painfully and embarrassingly familiar. It’s not uncommon with ADHD to feel as though you do everything for other people and receive so little in return, even when that’s not the objective reality, or when the other person involved could not be expected to know what you have done. It’s the model of deficit Gabor Maté talks about in Scattered Minds: you pay out more attention than you get back, regardless of whether others want your payments.

3. A Maddening World

Sarah: Someone has been changing my marks! What a horrible place this is! It’s not fair!

Door Knocker 1: That’s right. It’s not fair. But that’s only half of it.

Sarah: This was a dead end a minute ago.

Door Knocker 2: No, that’s the dead end behind you.

Sarah: It keeps changing. What am I supposed to do?

The routes and shapes of the labyrinth are amazing metaphors for the maddening actual and emotional spaces ADHD folks find themselves in. To take a few examples:

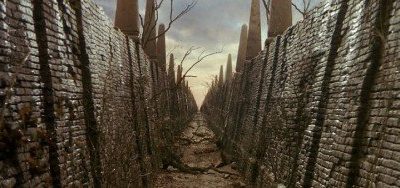

The Neverending Corridor

Sarah enters the labyrinth and finds herself in a dank brick alleyway which looks the same in both directions. She begins optimistically walking (“Come on, feet!”), but after a while it doesn’t appear she’s getting anywhere. She tries the other direction but finds the same story. Finally she tries running, to no avail. Exhausted, she flings herself at the walls, screaming and sobbing in frustration.

This rage at feeling trapped in a cycle of failure is once again very familiar, and could just as easily apply to someone stuck in a routine job that bores or exhausts them. It’s only when a friendly worm suggests Sarah is “just not looking right” that she uses her unusual perspective and discovers the myriad exits within the walls themselves.

The Oubliette

Sarah’s triumph at answering the door knockers’ riddle correctly is short-lived, as she drops straight into the oubliette. As Hoggle puts it, an oubliette is “a place where you put someone to forget about them”. On the way down, she is gripped and held in place by ‘Helping Hands’ – a brilliant metaphor for relying too much on others until their help becomes a paralysing, infantilising force. It is only her friendship with Hoggle that saves her. He sees her, remembers her and breaks her out of the hole, ensuring she is not forgotten forever.

The Bog of Eternal Stench

This is the most potent threat Jareth wields, and one that frightens Hoggle into escalating acts of betrayal against his only friend. As he puts it, “Dip so much as a foot into The Bog of Eternal Stench and you’ll smell bad forever.” The stench works as a metaphor for shame, a powerful emotion for Hoggle. Where is the moral event horizon for him, and how much will he abase and lose himself to fear before the shame catches up with him anyway?

The Junkyard of Memories

Upon breaking out of the hallucinatory ballroom, Sarah lands in a junkyard of all her old toys, inhabited by a snappy crone bent double and laden with junk. She is the witch to Sarah’s old princess persona, and a cautionary figure. The Junk Lady foists Sarah’s old things upon her, burdening her in the same way, and even invites her inside a replica of her old room. Initially comforted by the womblike space, Sarah wants to believe she is safely home, but she is too closely tethered to reality. Her mission comes back to her just in time and she resists the trap to rejoin her friends.

The Escher Room

In the final stand-off between Sarah and Jareth, she sees Toby at last, crawling through a room made of impossible staircases, heavily based on M.C. Escher’s artwork Relativity. There are nods to Escher’s motifs throughout the movie in the tesselating tiles of the maze, snakes and crystal balls.

In this room, Toby seems to be close at several points, only to vanish and appear in another place altogether. As Sarah pursues her brother, Jareth watches her and sings “Within You”, in which he angrily laments:

“How you turn my world, you precious thing.

You starve and near exhaust me.”

Distance and space obey Jareth’s manipulations, and he himself is able to defy the laws of physics, swinging up from beneath the platform on which Sarah stands, and even walking right through her. The confusion and panic she feels is very visceral for anyone feeling overwhelmed by their environment, emotions or problems.

It is only by leaping off the stairs and blindly into space – opting out of Jareth’s rigged game altogether – that Sarah destroys the illusion and escapes. Just as she did in the neverending corridor, she has used her creativity and impulsivity to break free.

4. Sarah Takes Responsibility

Hoggle: Them’s my rightful property. It’s not fair.

Sarah: No, it isn’t. But that’s the way it is.

The above quote is the first sign in the film that Sarah is evolving beyond raging-wounded-child mode, and assuming agency. She cheats Hoggle out of his jewellery as a practical move, and when faced with him echoing her own whine of “It’s not fair!” she realises that a) perhaps that’s true and b) that’s not the point.

Later, arguing with Sir Didymus over his arbitrary gatekeeping, she manages to break away from emotionally grappling with him and instead considers the wording of his vow, “that none may pass without [his] permission”. She then tries politely asking his permission. He is surprised, as nobody has ever asked this before in Jareth’s realm of conflict and confusion, and grants the request. By calming down, thinking and negotiating, Sarah not only gets her party across the bridge, but gains a loyal ally in the knight himself.

She also learns how to view things from others’ perspective, not just through the lens of her own pain. Hoggle, filled with self-loathing after giving Sarah Jareth’s amnesia peach, can hardly look at the friend he has betrayed. At this point Sarah chooses not to attack him but to recognise his anguish and shame, and forgive him; in doing so, she wins him back as a valuable friend and supporter.

It is only by subverting Jareth’s low expectations of her – and by extension, her own lack of self-belief – that Sarah finds herself in the Goblin City, much to the dismay of Jareth’s agents:

Guard : Your Highness! Your Highness! Your Highness, the girl! The girl who ate the peach and forgot everything!

Jareth : What of her?

Guard : She, the monster, Sir Didymus, and the dwarf, they made it through the gate and they’re on their way to the castle!

As the gang head into the castle to take on the final battle, Sarah stops them and takes responsibility for her own fate. Her friends acknowledge her autonomy but reassure her she has their support, reflecting the kindness, respect, trust and understanding she has built with them:

Didymus: [finally entering the castle] Well, come on then!

Sarah: No! I have to face him alone.

Didymus: But why?

Sarah: Because that’s the way it’s done.

Didymus: Well, if that is the way it is done, then that is the way you must do it. But, should you need us…

Hoggle: Yes, should you need us…

Sarah: I’ll call.

5. Growing Without Grieving

One of the most heartbreaking moments in the books I read as a sensitive, dreamy child was seeing characters exiled from the fantasy lands in which they had seen and done so much. It felt brutal to drag them back to a mundane world in which they were frequently misunderstood or held down, and force them to grow up within a strict template.

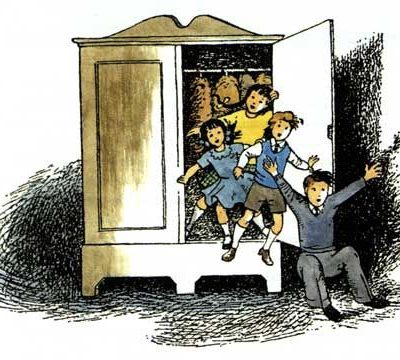

In Peter Pan, Wendy, John, Michael and even the Lost Boys abandon Peter in Neverland to become dull, staid Victorian adults, refusing their leader’s pleas to come back. In The Lion, The Witch & The Wardrobe, the Pevensies fight bravely and rise to royalty in Aslan’s lands, forgetting their old lives, only to wander back through the wardrobe door decades later and find themselves stripped of their achievements – the same awkward child evacuees who had wandered through in the first place.

I mourned the loss of so many magical friendships, the freedom of the adventure and the treasures won along the way. It didn’t seem fair that after saving the day, the child-hero was so unceremoniously booted out of their own story into the tiresome narrative of reality. This urge to cling to innocence and fantasy is often a way of replaying painful childhood memories; we hope that just one time we might skip the needle and heal the old wound. Peter Pan himself was a baby whose carriage rolled away from his parent-figure, and this trauma is evident in his refusal to leave Neverland and trust adults, even when he is offered love and security with the Darlings.

Meanwhile, once the world of the labyrinth has fallen down around the victorious Sarah, she finds herself back in her toy-filled room – for real this time. She has come safely home and Toby is sleeping next door, but the price of escape was the loss of her beloved friends.

As Sarah sits down in front of her mirror, she has a vision of Ludo sadly bidding her goodbye. She whirls around but no one is there. She turns back to the mirror and Sir Didymus greets her: “And remember fair maiden, should you need us…” Then Hoggle appears and echoes, “Yes…should you need us…for any reason at all…”

Tearfully, Sarah admits “I need you”, addressing first Hoggle, then all of the companions she has lost.

Traditionally, this would have marked the severing of ties: a sad realisation that she can only keep these friendships in her imagination. But Henson’s movie is merciful, nuanced and subversive, showing that you can grow as a person without killing your childhood joys. Take a look:

Labyrinth teaches us that we need to grow up and take ownership of our pain in order to conquer it, but that we can do this without crushing our playfulness, sensitivity, creativity, silliness, curiosity and eccentricity. These are traits we particularly associate with ADHD and neurodivergence, but they are present in everyone to different degrees, and should be treasured. What seems impossible may not be, and what seems like it will remain in place forever may be just about to shift and change. It’s what we do next that matters.

To quote a certain bescarfed worm:

“Things are not always what they seem in this place. So you can’t take anything for granted.”

Applause, applause! You are a beautiful writer and a beautiful soul, Kirsten Irving.